In STEM I, taught by Dr. Crowthers, all students perform an independent research project starting in August and ending at February Fair. In this class, we learn various practices done in real-life research such as grant writing, proposals, project planning, and proper research protocols. We start developing our ideas for these projects through brainstorming at the beginning of the year, after which we do research and investigate problems to narrow down our projects and start working on them. After we find all of our research, we test and acquire data, after which we use our technical writing skills to create a professional poster and paper to present our work.

Outline: The overall objective of this project was to design a robust facial identification system using fuzzy extractors and hypervectors. This was planned to be done by researching these technologies, iterating through the program to improve it as much as possible, and then comparing it to other technologies that are commonly used. The final statistics imply that the model runs at a satisfactory level of accuracy, although it does take quite a bit of time to do so. Through using technologies such as hypervectors and fuzzy signatures, biometric authentication can become more robust and useful than many currently used authentication models.

Current biometric security methods, while widespread, have prominent deficiencies.

This project aims to address these insecurities by writing a program to reinforce biometric authentication systems using two novel technologies: hyperdimensional vectors and fuzzy signatures.

We all know the importance of passwords. A good password can properly protect devices and accounts from attacks. However, most people do not set secure passwords; studies show that almost 60% of users create passwords including names or birthdays (ASEE 2022). Biometric authentication combats this and is used by many devices – including cell phones, keypads, computers, and locks – but many of these systems are not very secure, creating vulnerabilities. This compromises personal informational security, as it makes it more difficult to stop people from getting into devices. This project aims to solve these insecurities by writing a program to reinforce biometric authentication systems using two new technologies, hyperdimensional vectors and fuzzy signatures.

First, research was conducted in order to isolate the issues with biometric authentication systems. This is crucial because to improve the systems, their deficiencies must first be identified. To do this, various databases and journals – such as Scopus, IEEE, and Springer – were searched, indexed, and filtered through to find relevant articles. The internet was also searched in an attempt to find posts from users complaining about issues, but found issues with credibility and quantity, so these were not considered.

The next aim involved determining the optimal available version of the biometric authentication system by iterating through different versions, improving them as much as possible throughout. The initial version of the code for the system was first written. After testing it, its shortcomings were found and improved upon as much as possible. These improvements included substituting various modules in order to make everything work together properly. Throughout the course of this program, almost 15 different modules were used, many of which were later discarded in favor of others due to insufficient performance or compatibility issues. Then, to improve them, a new version of the program with theoretically improved performance was designed and tested it to see if it was any better.

The final aim here was to determine the viability of this project when compared with industry standard systems. The approach was to first test the system utilizing a data set. The expectations were that this would be obtained from volunteers, but because of certain issues that arose, this did not happen, and online datasets were used instead. After testing the system, the data was compiled and tested upon to see statistical values.

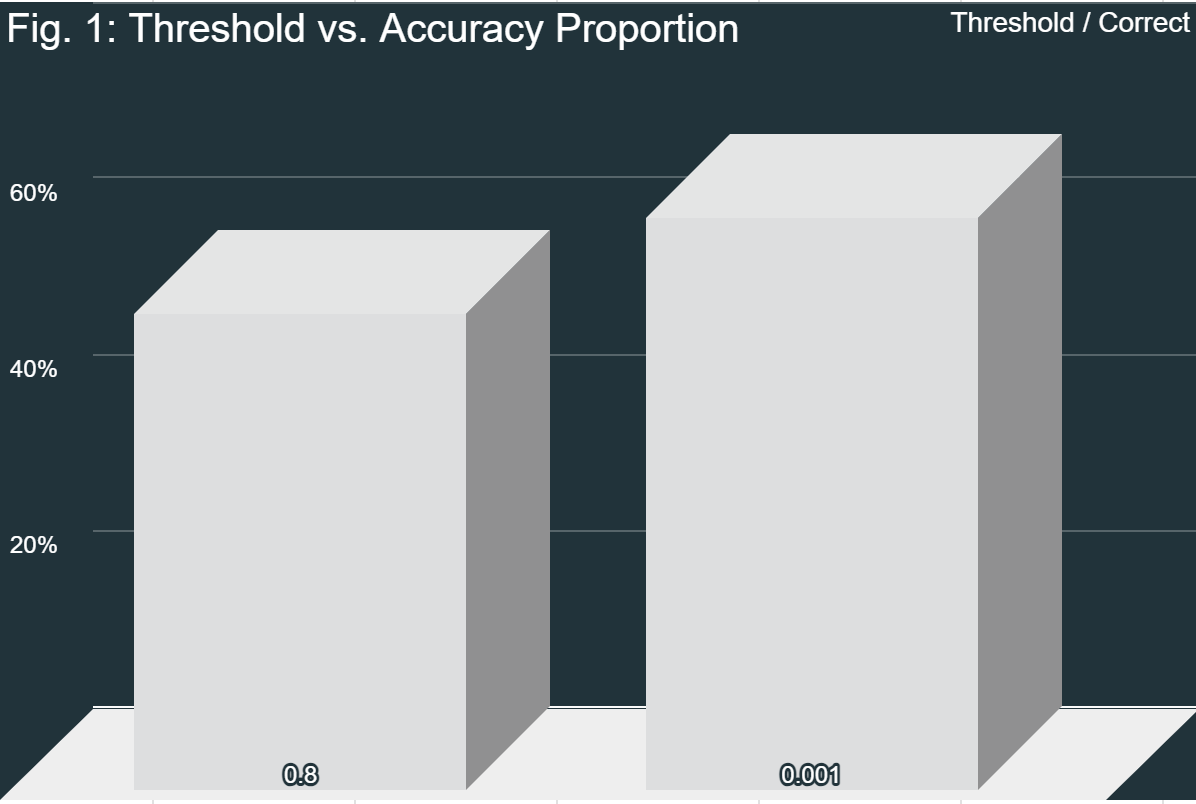

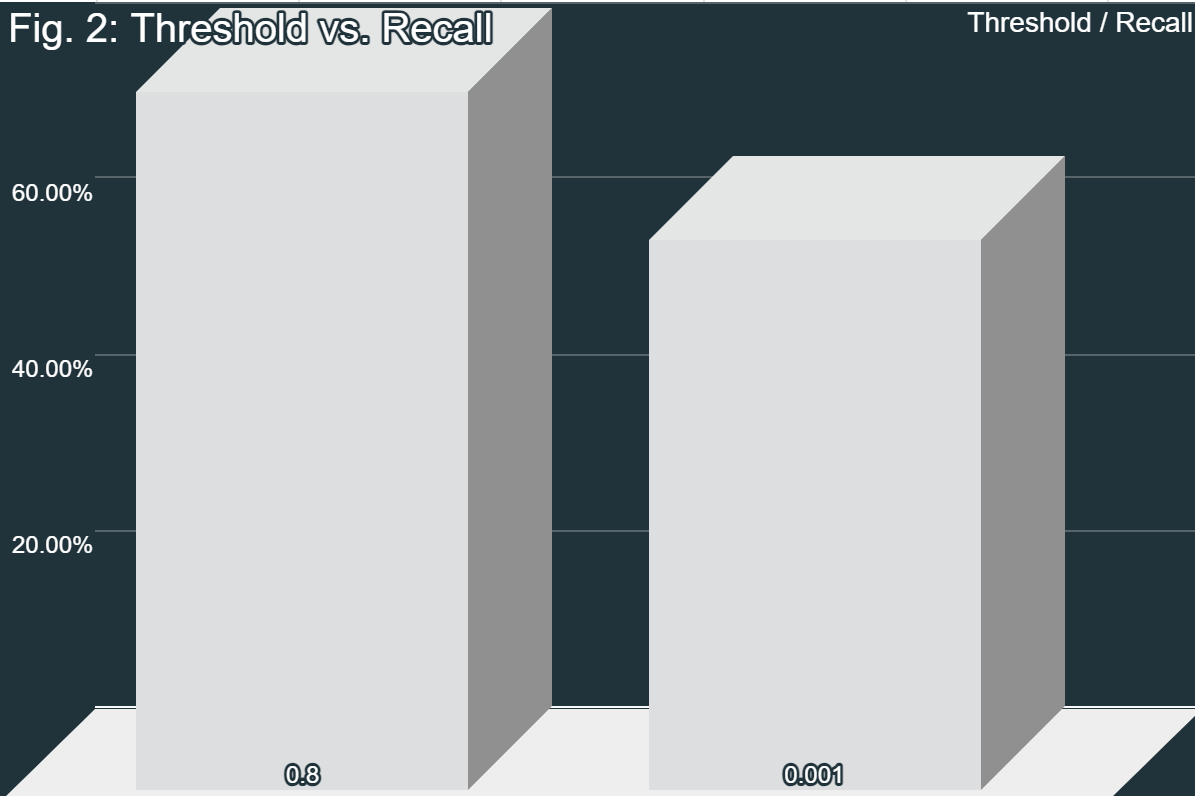

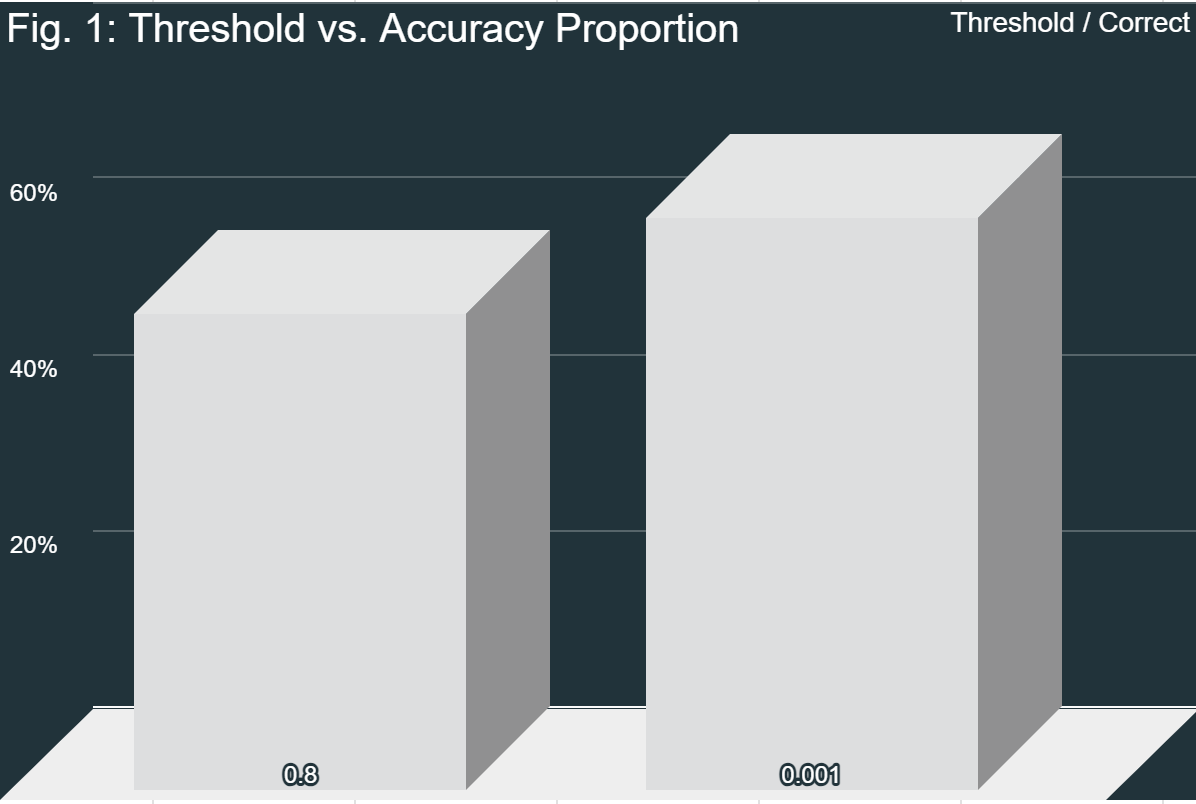

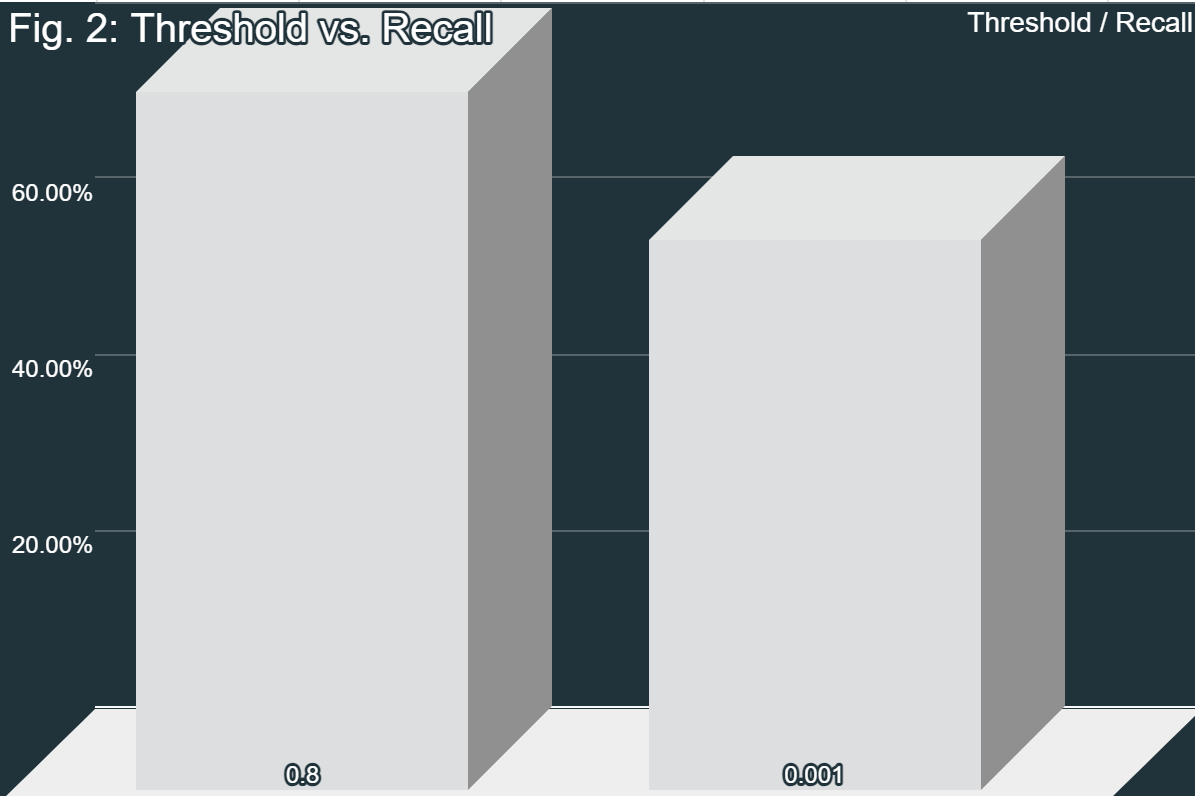

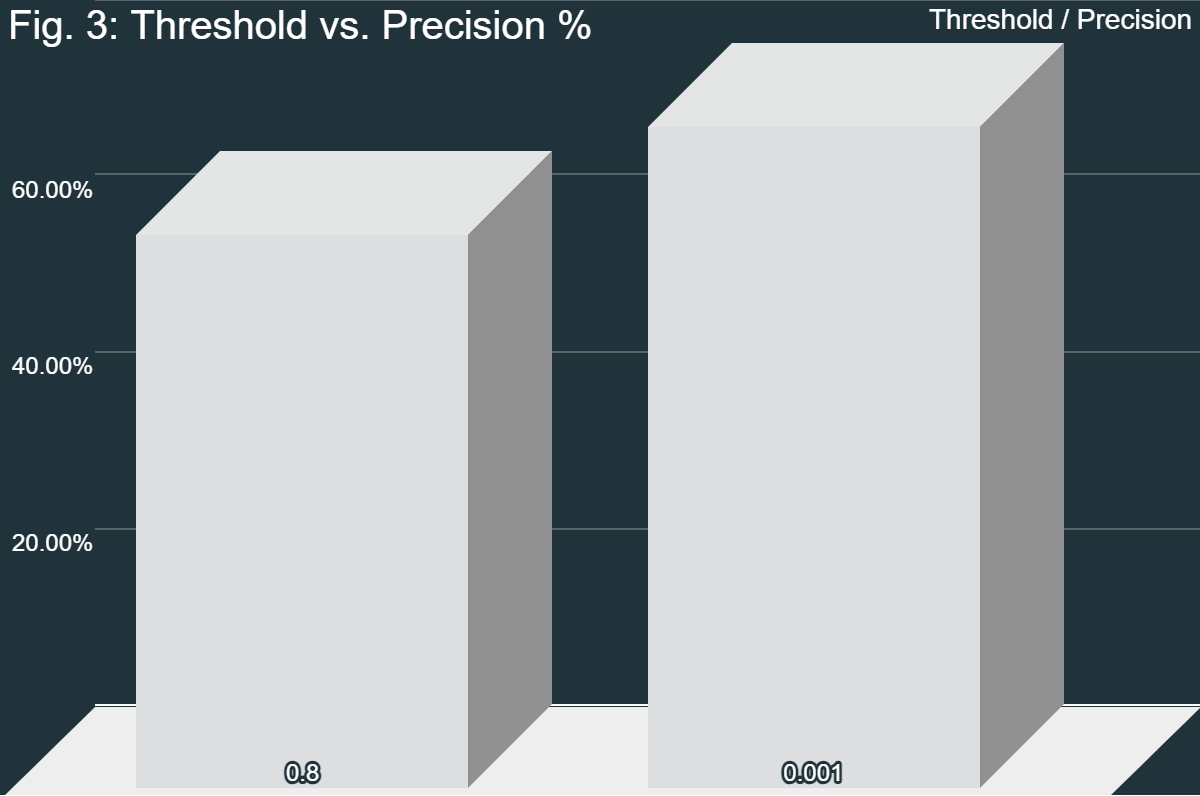

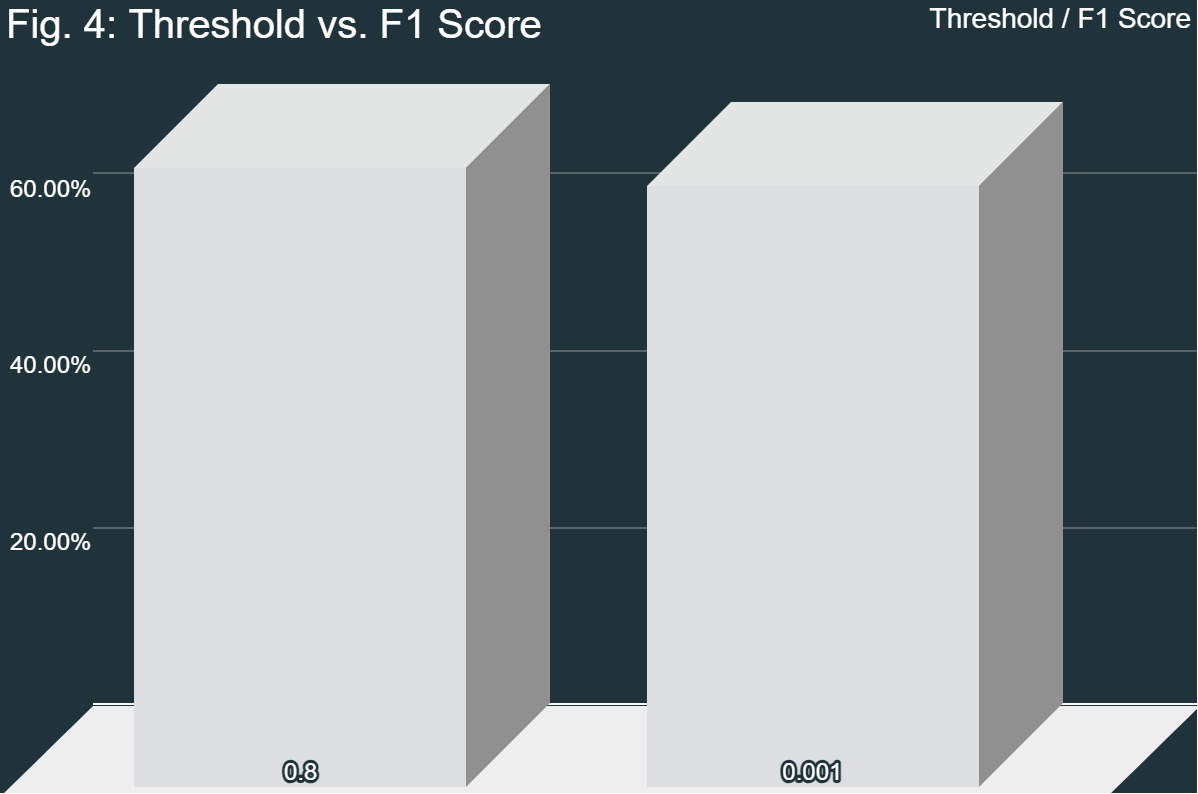

Both angle threshold values had their own issues. 0.8 was too lenient, resulting in extra false positives, while 0.001 was too strict, resulting in extra false negatives. However, when comparing the F1 scores, they were pretty similar. Therefore, because of the higher true correct-to-incorrect ratio with the second threshold, the system with that level is preferable. However, more testing needs to be done in order to find the point at which the Equal Error Rate is met; that is, where the number of false positives and false negatives is equal. Overall, the system is viable when compared to other current models. The only issue with the system is the time it takes to run.

Overall, the objectives of this project were both completed and not completed. The objective of this project was to design a model with fuzzy extractors and hypervectors. While the hypervectors were completely implemented as intended, the fuzzy extractor was not. Because of compatibility errors, standard fuzzy extractor algorithms could not be used. In lieu of these algorithms, the MediaPipe blendshape extraction was used. In fact, this could be classified as a form of fuzzy extractor; because the blendshape extractor analyzes the image and extracts the blendshapes, this is also a form of fuzzy extractor. The similarity check later on just builds on this equivalence. With a correct-to-incorrect proportion of 54%, the model was fairly accurate even in non-ideal conditions. Ideal conditions include good lighting, a good angle of the face towards the camera, no other faces in the image, and more. The model was able to deal with less-than-ideal conditions and maintain an F1 score (3) of 70.13%. An F1 score of 100% implies a perfect model that correctly identifies every face and perfectly minimized false positives and false negatives. Therefore, 70.13% represents a moderately performing model. Additionally, the Precision (1) and Recall (2) values are significant as well. A high precision value denotes that the system rarely makes mistakes and mostly returns true positives, and a high recall value denotes a high proportion of true faces that were correctly identified while minimizing false negatives. With a Precision of 62.79% and a Recall of 79.41%, while the model is not perfect, it is reasonably accurate in its judgements. Its accuracy is also comparable to many other models in non-ideal conditions (Crumpler, 2020). However, while this model may be sufficient for certain applications, such as those that are not highly secure (quick identification, etc.), its current state is not sufficient for higher-security applications.

Some limitations of this project include performance at significant head angles and time taken to run. As seen in Fig. 1, because the model relies on blendshapes, it can accurately define the positions of various landmarks and features on the face. However, this means that it is very susceptible to large deviations in angles. Because the tilt or turn of a person’s head can alter their features, the program struggles to deal with this. Similarly, because of the complexity of blendshape extraction, that portion of the program takes the longest time to run; on average, it took 13.23 seconds to isolate the blendshapes and sum their values. To put that into perspective, the hypervector section of the program took, on average, 0.011 seconds to run. However, the necessities of blendshape extraction do not allow us to improve this timing with the knowledge and technology currently available. There were many failures in this project, which were largely the causes of the high time taken as we could not spend more time to isolate the issues with blendshape extraction and streamline them. For example, the entire methodology of the code itself had to be changed almost 20 times before it finally worked how we wanted it to. This was because of many reasons, but chief among them were compatibility errors. There were far more compatibility errors than expected at the beginning of the project; enough that it took multiple weeks to iron them all out. While some of these were worked around, such as the hypervector module issues where we wrote our own implementation rather than using a popularly available one, others – like the fuzzy extraction modules – could not be implemented using the modules or written manually, so they needed to be slightly altered. In order to combat these compatibility errors, modules had to be swapped in and out many times.

The statistical test used was the one-sample z test. This test was chosen to see the reasonability of the 54% correct-to-incorrect rate that was obtained and ensure the validity of the other statistics like Recall, Precision, and F1 Score (Table 1). With a final p-value of 0.999999999, the results of the test were not statistically significant; this meant that there was not enough available evidence to reject the null hypothesis, which was that the true ratio of correct-to-incorrect results was 54%. In terms of fitting into past works, this project is built upon modules like MediaPipe that were created by others. It also utilizes technologies, especially hypervectors and facial blendshapes, that were discussed in past literature and projects (Ananthaswamy, 2023; Li et al., 2017). However, where it differs from other projects is in its usage of these technologies. Summing the blendshape scores and using the sum as a seed to generate hypervectors is an idea that has not come about before. Proving its viability increases the number of possibilities in the future for systems like this.

Future research would include increasing efficiency and accuracy. The most immediate way to do this would be to look at the blendshape extraction system. Because the current system takes such a long time to run, the program becomes much less viable. However, if this portion of the program can be isolated and improved, the full system will immediately become far more viable. Additionally, the accuracy would have to be increased. This could be done by lowering the threshold for similarity. Because there were more false positives than false negatives, that means that the threshold is most likely too high. Further future works would include lowering that threshold to increase accuracy.

The overall objective of this project was to design a robust facial identification system using fuzzy extractors and hypervectors. This was planned to be done by researching these technologies, iterating through the program to improve it as much as possible, and then comparing it to other technologies that are commonly used. The final statistics imply that the model runs at a satisfactory level of accuracy, although it does take quite a bit of time to do so. Through using technologies such as hypervectors and fuzzy signatures, biometric authentication can become more robust and useful than many currently used authentication models.

Ananthaswamy, A. (2023, April 13). A New Approach to Computation Reimagines Artificial Intelligence. Quanta Magazine. https://www.quantamagazine.org/a-new-approach-to-computation-reimagines-artificial-intelligence-20230413/.

American Society for Engineering Education. (2022, October 14). 15 password statistics that will change your attitude toward them. https://cybersecurity.asee.co/blog/password-statistics-that-will-change-your-attitude/

Crumpler, W. (2020, April 14). How Accurate are Facial Recognition Systems – and Why Does It Matter? Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/blogs/strategic- technologies-blog/how-accurate-are-facial-recognition-systems-and-why-does-it

Dodis, Y., Ostrovsky, R., Reyzin, L., & Smith, A. (2008). Fuzzy Extractors: How to generate strong keys from biometrics and other noise data. SIAM Journal on Computing, 38(1), 97-139. https://epubs.siam.org/doi/10.1137/060651380

Lewis, J. P., Anjyo, K., Rhee, T., Zhang, M., Pighin, F., & Deng, Z. (2014). Practice and Theory of Blendshape Facial Models. Eurographics, doi.org/10.2312/egst.20141042

Li. N., Guo, F., Mu, Y., Susilo, W., & Nepal, S. (2017). Fuzzy Extractors for Biometric Identification. IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), 667-677. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDCS.2017.107

Naganuma, K., Suzuki, T., Yoshino, M., Takahashi, K., Kaga, Y. & Kunihiro, N. (2020). New Secret Key Management Technology for Blockchains from Biometrics Fuzzy Signature. Proceedings of the Asia Joint Conference on Information Security. 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1109/AsiaJCIS50894.2020.00020.

Rountree, D. (2013). Biometric Authentication. Federated Identity Primer, 13-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407189-6.00002-9

Wang, Y., Li, B., Zhang, Y., Wu, J., Liu, G., Li, Y., & Mao, Z. (2023). A Novel Blockchain’s Private Key Generation Mechanism Based on Facial Biometrics and Physical Unclonable Function. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2023.103610.