Leslie Population Models

Ma 2071

Problem: use

linear algebra to predict the growth and characteristics of a population which

is broken into age groups. This will

illustrate the numerical use of diagonalization. Conference yesterday

illustrated a geometric use of diagonalization.

Knowing the total population is good but knowing how it is distributed among different age groups

is better. Different groups have different social and economic needs which need

planning and resources for:

- young

children need daycare

- older

children need schools, playgrounds

- adults

provide taxes, have jobs, buy houses and consumer goods, and purchase

and drive cars

- older

adults require health care and different housing

- industries

need utilities, good roads and zoning

The general

study of these characteristics is called demographics. It is of concern to civil engineers who must

plan public utilities, computer scientists who provide information services,

mechanical engineers who design transportation media such as cars and trains,

electrical engineers who must provide adequate electricity, biotech people who

provide solutions to the unique health needs of each group, and mathematicians

(as actuaries) who work with various kinds of insurance needed by all groups

(auto, life, house, health). Electrical

and computer engineers also need markets for consumer goods they design such as

computer games, Internet access, high definition television and cell

phones.

In this course,

the Bio majors are looking at the spread of HIV and also what it might take to

effectively change that.

Quantitative

models are of considerable value.

Knowing in advance that the population of 20 to 30 year olds is going to

decline by 2% is of value to an auto manufacturer who has a line of sports

cars. In

______________________________________________

The mathematics: x is a

column vector with the size of the population for each group as its

components. In this hypothetical model,

the first component of x might be the number of 0 to 25 year olds, the second

component 26 to 50 year olds, the third 51 to 75 year olds and the last 76 year

old or more.

The future populations are generated according to the

matrix model

x(k+1) = A x(k)

A is called a Leslie Matrix. It has birthrates of each of the age groups along

the top row and has survival percentages along the subdiagonal.

It is 4x4 in this instance. I will use Maple to study

this below…

> with(linalg):

Warning, the

protected names norm and trace have been redefined and unprotected

> with(plots):

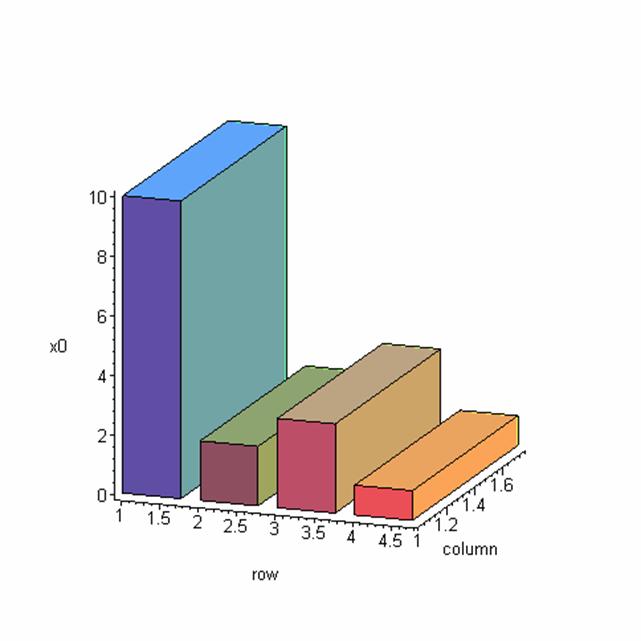

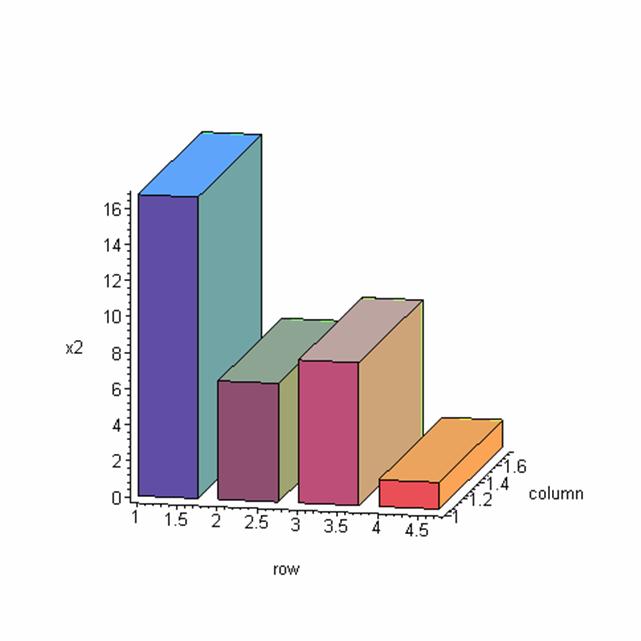

Intitial Population - divided into

4 age groups

(lots of young

people)

Warning, the name

changecoords has been redefined

> x0:=matrix(4,1,[10,2,3,1]);

This can be displayed in histogram form:

> matrixplot(x0,heights=histogram,axes=frame,gap=0.25,style=patch);

The following matrix is used to compute the population one

generation into the future.

> A:=matrix(4,4,[.2,1.5,.7,.2,.9,0,0,0,0,.88,0,0,0,0,.84,0]);

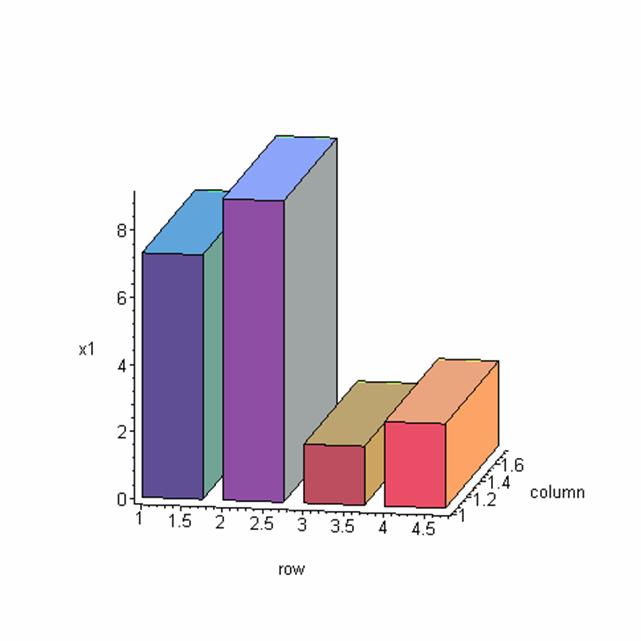

Transient Behavior - what happens in the immediate future:

![]()

> x1:=multiply(A,x0);

> matrixplot(x1,heights=histogram,axes=frame,gap=0.25,style=patch);

> x2:=multiply(A,x1); 2 units of time into the future

>

> matrixplot(x2,heights=histogram,axes=frame,gap=0.25,style=patch);

Now let's look further into the future; 10

units of time.

> x10:=multiply(A^9,x0);

> x11:=multiply(A^10,x0);

Let's compare how each component of the population has

changed:

> ratio1:=x11[1,1]/x10[1,1];

![]()

> ratio2:=x11[2,1]/x10[2,1];

![]()

> ratio3:=x11[3,1]/x10[3,1];

![]()

> ratio4:=x11[4,1]/x10[4,1];

![]()

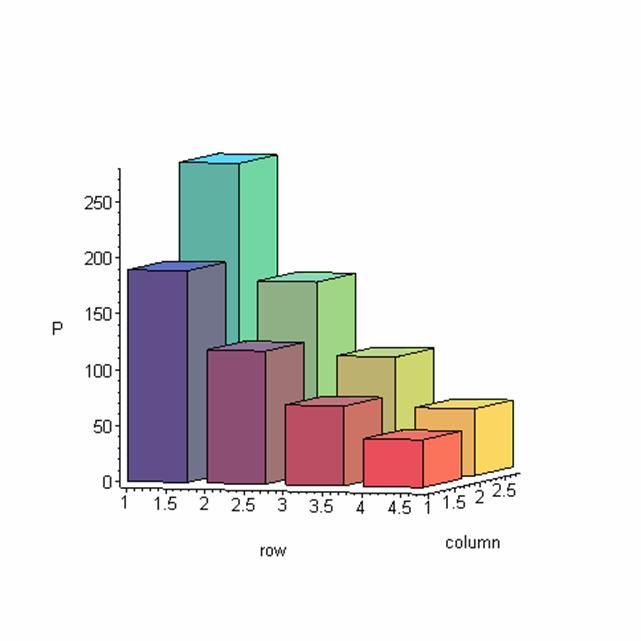

Next, we plot both populations on the same histogram:

> P:=augment(x10,x11):

> matrixplot(P,heights=histogram,axes=frame,gap=0.25,style=patch);

What does this last histogram show? It shows that the shape remains the same, from one period of time to the next. All groups increase in size but they increase

in size by the same factor (1.44)

What does this have to do with diagonalization? The vector made up of the sizes of the age

groups is an eigenvector of A. The

factor that they increase by is an eigenvalue of A, 1.45. More specifically, it is the

largest of the four eigenvalues of A, the dominant

eigenvalue.

What the above histogram shows is algebraically shown as

x(11) = 1.45 x(10)

and since

x(11) = A x(10)

this means 1.45 is an

eigenvalue of A and x(10) is its eigenvector.

Furthermore, this behavior continues indefinitely. This means x(21) = 1.45 x(20) or

x(25) = 1.45 x(24). In other

words, the shape of the histogram remains the same and the population increases

by a factor of 1.45 each time (i.e. goes up by 45%)

The moral? If we know the

largest eigenvalue and its eigenvector for a dynamical system, then we know

what the long term behavior of the system will be.

The profile of the solution will be determined by the eigenvector

The rate of growth will be determined by the eigenvalue.

These remarks apply to any dynamical system of the

form x(k+1) = A x(k).

All of this can

be quickly predicted by computing the eigenvalues and

eigenvectors of A:

> eigenvectors(A);

Amidst

this barrage of data is a largest eigenvalue, 1.444463... and its

eigenvector, [.79, .49, .3 , .175] Its components have the same relative size

as x(11) and x(10) above (you might check this with a calculator!)

To see why it

works out this way, we need to look at the basic equation A

= P D P-1 We will do that

Friday…